A while back, I spent a few weeks designing the new access control system for our infrastructure. Three environments, multiple teams, a permissions model complex enough that every approach I tried had some trade-off I couldn’t fully resolve. I’d landed on something I felt solid about.

Then, in the design review, a teammate suggested a different model — simpler access boundaries in lower environments, with resource-level policy enforcement handling the sensitive parts. Five minutes into his explanation, I knew he was right. His model let engineers roam freely across lower environments — not locked to their own namespaces — which meant debugging a cross-service issue no longer required hunting down someone from another team to pull logs for you. His approach was better.

My first reaction was to defend mine anyway.

Not loudly. Not stupidly. I pushed back moderately, documented all the approaches, and kept things professional. But internally, I caught myself doing something worth naming: I was bothered, not by the logic of his idea, but by the fact that it was his.

The pattern and the reframe

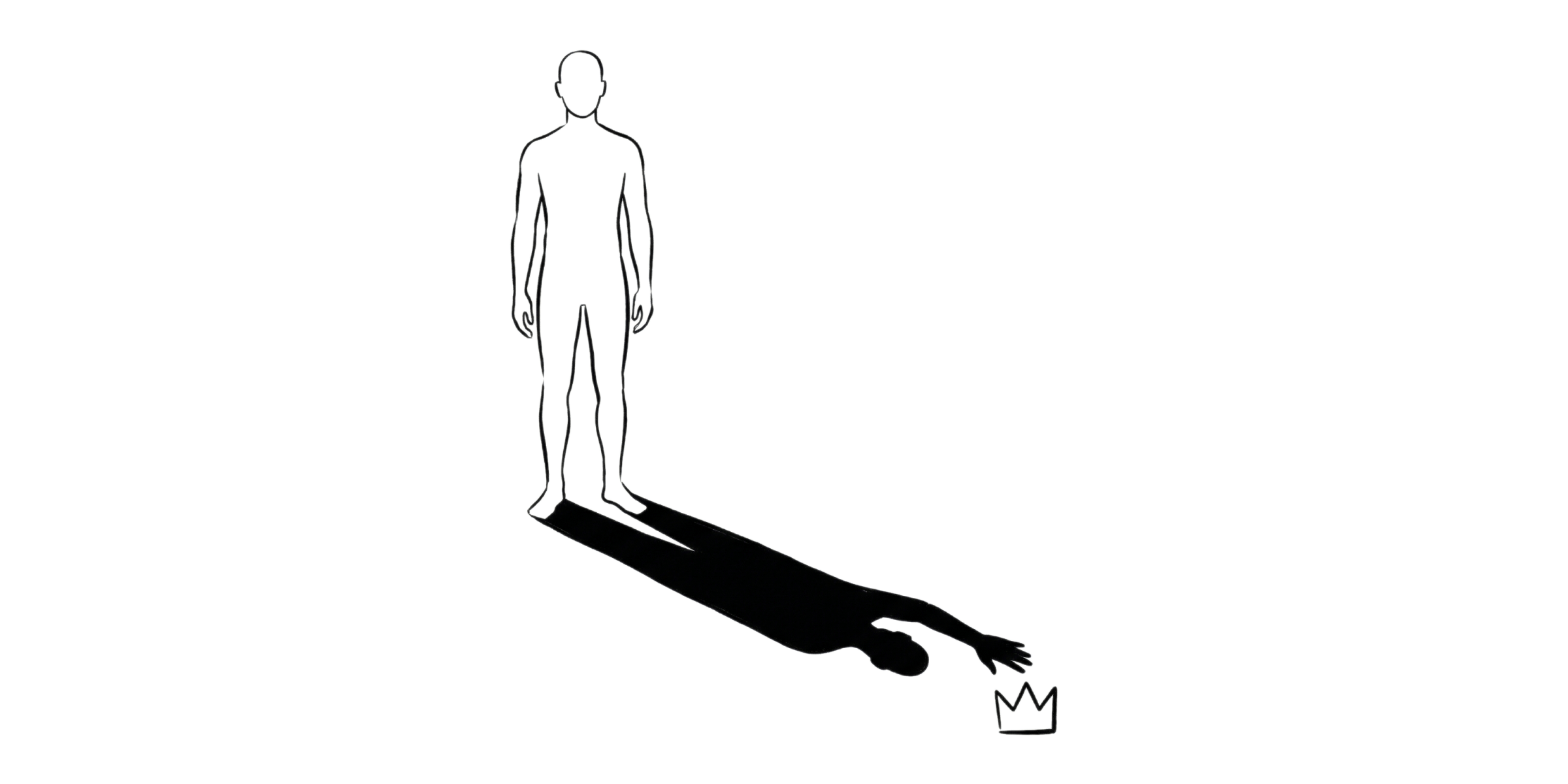

At senior levels, most of us have been the person with the best technical ideas in the room for long enough that it becomes part of how we measure ourselves. We don’t just want good outcomes — we want to be the source of them. When someone else generates a better idea, it registers, somewhere below rational thought, as a small loss.

I’d call this positional dominance: needing to have the best ideas to feel like you’re leading. It’s zero-sum by design. Every peer’s strong contribution feels like a threat to your position, because in this frame, there’s only one winner per decision.

It’s also exhausting. And it quietly makes you worse at your job.

“Be humble” or “let others shine” are just positional thinking with better PR. The real shift is changing what you’re optimizing for.

Outcome dominance: You win when the project wins. Full stop.

If that means your design gets replaced by something better, you still win — because you led the process that surfaced the better design. The peer’s idea was raw material. Your leadership turned raw material into a shipped, working system.

The next morning

The day after, I reviewed my notes. His approach was clearly better. It would simplify implementation without compromising what actually needs to be protected. I dropped my design and wrote up his.

That choice — and the lack of resentment I felt making it — is what outcome dominance actually feels like in practice.

What leadership actually is at Staff level

This reframe only holds if you’re clear on what your leadership contribution actually is. Because if you think leadership = best ideas, then giving up your idea feels like giving up your role.

I had been leading that project for weeks before that meeting. Here is what that looked like:

- Identified the problem and defined what “good” looked like

- Brought the right people into the design conversation

- Synthesized the options into a coherent decision

- Was accountable for delivery

None of that changed because his model was better than mine. That list is the leadership contribution. A peer’s ideas are inputs to that process, not competition with it.

The engineer who comes up with a good idea in a meeting isn’t leading the project. You are. Those aren’t in conflict — they’re complementary.

The practical test

Here’s how I know when I’ve actually internalized this vs. just telling myself a nice story about it:

Can I say “their approach was better, and I’m glad we went with it” — out loud, to the team, without any residue of resentment?

If yes: outcome dominance. If I’m still quietly keeping score, looking for ways to qualify the credit, or framing it as “we ended up going with a combined approach” when we really just used theirs — I’m still optimizing for position.

The honest answer, in that RBAC project, was yes. His model shipped. It made the system simpler. That’s the outcome I was responsible for delivering. I delivered it.

The messy parts

This isn’t a one-time switch. The positional response is fast and automatic — it fires before the rational brain catches up. The work is noticing it when it happens, not preventing it from happening at all.

Also: documenting competing approaches before making a call, as I did in that meeting, is one of the most useful habits I’ve developed. It creates a day’s distance between the emotional reaction and the decision. That gap is where clear thinking lives.

And one more thing: outcome dominance doesn’t mean your ideas don’t matter or that you should drop them at the first sign of pushback. Sometimes your design is right and needs defending. The difference is whether you’re defending it because the logic holds, or because it’s yours.

There’s also a quieter fear worth naming: if the idea that shipped wasn’t mine, what do I point to in a performance review?

This is real, especially when promo cycles reward visible output. But a peer’s idea appearing in the final design isn’t an absence of your leadership — it’s evidence that your process worked.

What’s actually worth making visible is the upstream work: you defined the problem, you ran the review that surfaced the better approach, you synthesized the options, and made the call. Document that, not the idea. If you led the process that produced the outcome, that’s what you put in front of your manager — and it’s a stronger case than “my design shipped” ever was.

The lesson

What’s more rare — and what actually scales — is creating conditions where the best ideas, regardless of source, reliably surface and ship.

The metric isn’t “did my idea win?” It’s “did the right outcome happen, and did I lead the process that got us there?”

You can be the smartest person in the room, or you can be the person who made the room smarter. At Staff level, only one of those scales.