In this blog post, I’m excited to share some valuable system design insights drawn from AWS’s post-event summaries on major outages.

System design is a topic I’m especially passionate about—it’s even my favorite interview question at Grammarly, and I love to conduct those interviews. This fascination led me to thoroughly analyze AWS’s PES in search of the most interesting cases.

Learning from mistakes is essential. Yet it’s precious to learn from others’ mistakes because they come for free (for you, but not for their owners). The AWS team is doing a great job sharing their Post-Event Summaries because they not only demonstrate the open engineering culture but also help others.

From the sixteen reports available at the time of writing, I’ve selected the four most captivating ones. Each presents unexpected challenges and turns of events, along with valuable outcomes we can learn from. Let’s explore these intriguing reports and uncover the key strategies for building more resilient systems.

Remirroring Storm

The April 21, 2011, Amazon EC2/EBS event1 in the US East Region provides valuable insights into dependency management and the dangers of cascading failures.

A network configuration change, promoted as a part of normal scaling activity, set off a cascade of failures in the Amazon Elastic Block Store system. The intention was simple — to upgrade the capacity of the primary network. This operation involved a traffic shift between underlying networks, but it was executed incorrectly so that change caused many EBS nodes to disconnect from their replicas. When these nodes reconnected, they tried to replicate their data on other nodes, quickly overwhelming the EBS cluster’s capacity. This surge, or as AWS called it “remirroring storm,” left many EBS volumes “stuck,” unable to process read and write operations.

Blast Radius: Initially, the issue affected only a single Availability Zone in the US East Region, and about 13% of the volumes were in this “stuck” state. However, the outage soon spread to the entire region. The EBS control plane, responsible for handling API requests, was dependent on the degraded EBS cluster. The increased traffic from the remirroring storm overwhelmed the control plane, making it intermittently unavailable and affecting users across the region.

Affected Services and Processes:

- EC2: Users faced difficulties launching new EBS-backed instances and managing existing ones.

- EBS: Many volumes became “stuck,” rendering them inaccessible and impacting EC2 instances dependent on them.

- RDS: As a service dependent on EBS, some RDS databases, particularly single-AZ deployments, became inaccessible due to the EBS volume issues.

This incident underscores the importance of building resilient systems. The EBS control plane’s dependence on a single Availability Zone and the absence of back-off mechanisms in the remirroring process were critical factors in the cascading failures.

Electrical Storm

The June 29, 2012, AWS services event2 in the US East Region exemplifies how a localized power outage can trigger a region-wide service disruption due to complex dependencies.

A severe electrical storm caused a power outage in a single data center, impacting a small portion of AWS resources in the US East Region — a single-digit percentage of the total resources in the region (as of the date of the incident).

Blast Radius: The power outage was initially confined to the affected Availability Zone. However, it soon led to degrading service control planes that manage resources across the entire region. While these control planes aren’t required for ongoing resource usage, their degradation hindered users’ ability to respond to the outage, such using the AWS console to try moving resources to other Availability Zones.

Affected Services and Processes:

- EC2 and EBS: Approximately 7% of EC2 instances and a similar proportion of EBS volumes in the region were offline until power was restored and systems restarted. The control planes for both services were significantly impacted, making it difficult for users to launch new instances, create EBS volumes, or attach volumes in any Availability Zone within the region.

- ELB: Although the direct impact was limited to ELBs within the affected data center, the service’s inability to process new requests quickly hampered recovery for users trying to replace lost EC2 capacity in other Availability Zones.

- RDS: Many Single-AZ databases in the affected zone became inaccessible due to their dependent EBS volumes being affected. A few Multi-AZ RDS instances, designed for redundancy, also failed to failover automatically due to a software bug triggered by the specific server shutdown sequences during the power outage.

Even though we host our applications in the cloud and power outages may not be a primary concern when starting new projects, this event underscores the critical importance of designing fault-tolerant systems. It also highlights the potential for cascading failures when a small percentage of infrastructure is impacted. Dependencies on control planes and the interconnected nature of services can significantly amplify the impact of localized outages.

Simple Point of Failure

Another excellent example of how small can quickly become big — is the Amazon SimpleDB service disruption on June 13, 2014, in the US East Region3. This incident demonstrates how a seemingly minor issue can escalate into a significant disruption due to dependencies on a centralized service.

A power outage in a single data center caused multiple storage nodes to become unavailable. This sudden failure led to a spike in load on the internal lock service, which manages node responsibility for data and metadata. And while this lock services is replicated accross multiple data centers, the load spike wat too sudden and too high.

Blast Radius: Initially, the impact was confined to the storage nodes in the affected data center. However, the increased load on the centralized lock service, crucial for all SimpleDB operations, caused cascading failures that affected the entire service.

Affected Services and Processes:

- SimpleDB: The service became unavailable for all API calls, except for a small fraction of eventually consistent read calls, because the storage and metadata nodes couldn’t renew their membership with the overloaded lock service. This unavailability prevented users from accessing and managing their data.

This outage highlights the critical importance of addressing the single point of failure when designing systems. The centralized nature of the lock service, intended for coordination, became a single point of failure. A more distributed or load-balanced approach for the lock service could have mitigated the impact of the simultaneous node failures.

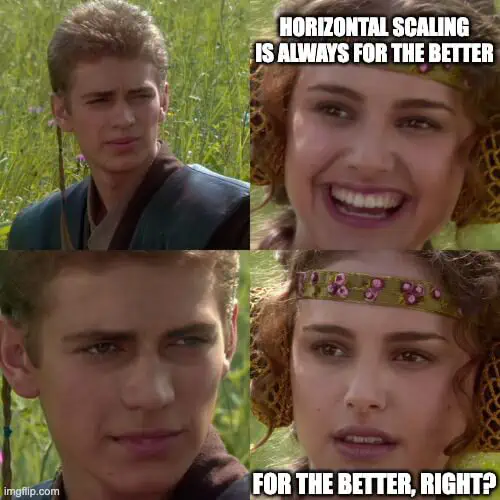

Scaling for the better

In search of absolute

The Amazon Kinesis event in the US East Region on November 25, 20204, is a perfect example of how adding capacity can unexpectedly trigger a cascade of failures due to unforeseen dependencies and resource limitations. What could possibly go wrong by adding more nodes to the cluster? Scaling horizontally is best practice, right? Well, it depends.

A small capacity addition to the front-end fleet of the Kinesis service led to unexpected behavior in the front-end servers responsible for routing requests.

These newly added servers exceeded the maximum allowed threads due to operating system configuration: each front-end server creates operating system threads for each of the other servers in the front-end fleet — this is needed for services to learn about new servers added to the cluster. Eventually, all this caused cache construction failures and prevented servers from routing requests to the back-end clusters.

Blast Radius: Although the initial trigger was a capacity addition intended to enhance performance, the resulting issue affected the entire Kinesis service in the US East Region. The dependency of many AWS services on Kinesis amplified the impact significantly.

Affected Services and Processes:

- Kinesis: Customers experienced failures and increased latencies when putting and getting Kinesis records, rendering the service unusable for real-time data processing.

- Cognito: As a dependent service on Kinesis, Cognito faced elevated API failures and increased latencies for user pools and identity pools. This disruption prevented external users from authenticating or obtaining temporary AWS credentials.

- CloudWatch: Kinesis Data Streams are used by CloudWatch to process metrics and log data. The event caused increased error rates and latencies for CloudWatch APIs (PutMetricData and PutLogEvents), with alarms transitioning to an INSUFFICIENT_DATA state, hindering monitoring and alerting capabilities.

- Auto Scaling and Lambda: These services rely on CloudWatch metrics, so they were indirectly affected, too. Reactive Auto Scaling policies experienced delays, and Lambda function invocations encountered increased error rates due to memory contention caused by backlogged CloudWatch metric data.

This incident highlights the importance of thoroughly understanding dependencies, resource limitations, and potential failure points when making changes to a system, even those intended to improve capacity or performance. Robust testing and monitoring are crucial to identify and mitigate such unexpected behaviors.

Final Thoughts

The AWS outage reports reveal a fundamental truth about system design: complexity and interdependency can be both our greatest strengths and our most significant vulnerabilities.

As we build and scale our systems, let’s strive for simplicity, resilience, and a thorough understanding of our dependencies.

To ensure our systems are prepared for the unexpected, it’s crucial to internalize and act upon the lessons these incidents teach us. Here are some key takeaways to guide us in this:

- Embrace Resilience: Design systems with robust fault-tolerance mechanisms to handle unexpected failures without cascading effects.

- Understand Dependencies: Map out and regularly review your system’s dependencies to identify and mitigate potential single points of failure.

- Continuous Learning: Analyze past incidents, both your own and industry-wide, to gain insights and improve your system design.

- Proactive Monitoring: Implement comprehensive monitoring and alerting to detect and address issues before they escalate.

- Thorough Testing: Regularly test your systems under various failure scenarios to ensure they can withstand real-world conditions.

The path to reliable systems is paved with continuous learning and adaptation. Let’s embrace these lessons and push the boundaries of what our systems can achieve, ensuring that we are always prepared for the unexpected. 🙂

Summary of the Amazon EC2 and Amazon RDS Service Disruption in the US East Region, April 21, 2011 ↩︎

Summary of the AWS Service Event in the US East Region, June 29, 2012 ↩︎

Summary of the Amazon SimpleDB Service Disruption, June 13, 2014. ↩︎

Summary of the Amazon Kinesis Event in the Northern Virginia (US-EAST-1) Region, November 25, 2020 ↩︎